By Alan Munro

Oysters being put in the loch by local community © Philip Price

Once upon a time, Scotland’s inshore seas supported vast seagrass meadows rich in biodiversity and oyster reefs that extended over several kilometres. They provided three-dimensional complexity to an otherwise muddy sea floor.

But since the days of industrialisation these habitats have all but disappeared from our waters: pollution, bottom-contact fishing, coastal development and, most recently, climate change, have brought both seagrass and oysters to the brink.

And yet these habitats have enormous potential to deliver valuable services to humans, including protecting coasts from flooding and erosion, improving water quality, supporting fisheries production, and capturing and storing carbon. This last service is receiving a lot of airtime as we look to nature to help address the climate crisis.

Armed with a greater understanding of the extent to which our seas are degraded, and the vital role of marine habitats in helping meeting Scotland’s commitments on climate and biodiversity, a movement has emerged with a goal to restore what has been lost.

What is restoration?

Ecosystem restoration is broadly defined in the scientific literature as “the process of assisting the recovery of damaged, degraded, or destroyed ecosystems” and the UN declared 2021-2030 as the UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration to respond to the growing nature and climate crises.

It is increasingly recognised that we need to complement efforts to preserve what is left of habitats (e.g. by removing human pressures and creating protected areas), with active restoration efforts that accelerate natural regeneration. Of course, the two approaches are not mutually exclusive and both should form part of a broader strategy for marine recovery.

Examples of ecosystem restoration in the marine realm include re-seeding the seabed with native oysters or replanting seagrass meadows.

Marine restoration in Scotland

Pioneering restoration projects have already sprung up around Scotland’s coasts (see map below). Seawilding, a local charity based at Loch Craignish in Argyll, is the UK’s first community run marine restoration project, which aims to reintroduce native oysters and restore seagrass to the loch. Other projects are taking place in Lochaline, Loch Melfort, and the Firth of Clyde.

Community-led approaches to restoration such as this offer exciting, locally-specific visions for achieving marine habitat recovery in Scotland. But if we want to achieve recovery at the level of the ecosystem, local efforts need to be scaled up. How do we achieve this without compromising the grassroots way projects have emerged? And is there an appetite for a more integrated approach to marine restoration?

The study

I joined Fauna & Flora International as an intern to explore marine restoration activity in Scotland and explore the motivations, challenges and aspirations of a number of existing and planned marine restoration projects to determine whether ambition exists for a more holistic vision of marine restoration in Scotland.

Over the course of the study I managed to talk to a number of individuals, from those engaged (or planning to engage) in marine restoration activity to NatureScot and WWF-UK.

Key findings

Motivations to restore

Framing marine restoration in ways that resonates with communities and their needs is much more likely to leverage community support. This means that we need to understand why particular groups decide to restore marine habitats. Groups in this this study were found to be motivated to restore for both ecological and social reasons, including: repairing local degraded ecosystems to enhance biodiversity and provide ecosystem services (e.g. improving local water quality), delivering local livelihood benefits (e.g. job and education opportunities), and promoting opportunities to reconnect local people to the sea. This latter point is important when we think more broadly about how we can foster local marine stewardship.

“I can see that restoration projects are a very interesting, practical opportunity to really engage sectors of the community in more practical activities involved with the sea.”

Challenges to overcome

It was apparent that all marine restoration projects face numerous challenges that, if not addressed, might stifle marine restoration practice.

First and foremost was the issue of community capacity, with some groups relying on the goodwill and enthusiasm of local volunteers to initiate and run projects. Restoration can be a complex and time-consuming process that requires up to a year of planning and baseline surveying, not to mention the ongoing monitoring that is needed once a project has started. Paid capacity is something that needs more consideration.

Similarly, the costs of restoration are likely to be beyond what many community groups can reasonably fundraise, especially for non-constituted groups. Current funding for restoration – mostly third sector and government grants – tends to be for short durations, whereas restoration is a long-term endeavour (up to 10 years to restore an oyster reef!).

Cumbersome, lengthy and confusing permitting and licensing processes were found to delay projects, partiuclarly since marine restoration techniques remain an unfamiliar area for local authority planners.

The lack of readily-accessible local data to help identify restoration opportunities was pointed out to be potentially inhibiting for getting projects off the ground. Communities need a baseline understanding of potential sites for restoration to both understand whether a project is likely to be successful or not, and to provide a benchmark against which to measure future changes to the local environment.

“In terms informing an understanding of where your opportunities might be for restoration, I actually think it’s quite challenging for communities to get to the bottom of what information is already exists.”

Another key concern for individuals engaged in marine restoration is how to ensure sites being restored are protected from damaging activities, such as bottom-contact fishing. There are currently few options for communities to pursue to protect their restored sites, particularly if these sites are not already within an existing Marine Protected Area. There needs to be a focus on integrating marine restoration activities into wider seas management.

“And you know what, why are we bothering if they’re going to keep on allowing these trawlers and dredges to come in and allowing the expansion of a very unsustainable [salmon farming] industry?”

Aspirations

There was consensus that communities are best placed to manage marine restoration. Many projects are already involving local community members in restoration through citizen science, educational outreach and volunteering activities. Participants discussed how mobilising people to engage in grassroots level action can create a sense of ownership of the seabed, which in turn helps secure long-term interest in its protection and sustainability. It’s also a tangible way for communities to address global crises.

“We can’t save the planet. But you can do your little bit in your backyard…and I think there’s strength in that, and there’s resilience, and there’s sustainability”

A community-led model, involving groups of passionate, committed individuals providing informal peer-to-peer support, is one which has enormous potential for replication at scale, if adequately resourced. However, as projects increase in spatial scale, they require greater levels of planning, coordination and financing. These can be gained by forming collaborative partnerships with other actors. Restoration Forth demonstrates a potential partnership model with a large-scale restoration focus where community hubs act as a foci for on-the-ground project design and delivery while funding and overall coordination is provided by NGOs. The key is to ensure that local community groups are viewed as equal, autonomous partners in project design and delivery.

Scaling up also requires strategic direction and support. Communities are currently having to “go it alone” and there is as yet no mechanism to align goals and approaches, or to capture and address some of the challenges identified in this study. Any form of national input or oversight must be careful, however, not to undermine or restrict the bottom-up approach to marine restoration that has emerged in Scotland. Local measures that promote recovery of Scotland’s marine environment need to be recognised and valued as not only good for local communities, but for society at large, and community-based groups should be incentivised to implement restoration efforts.

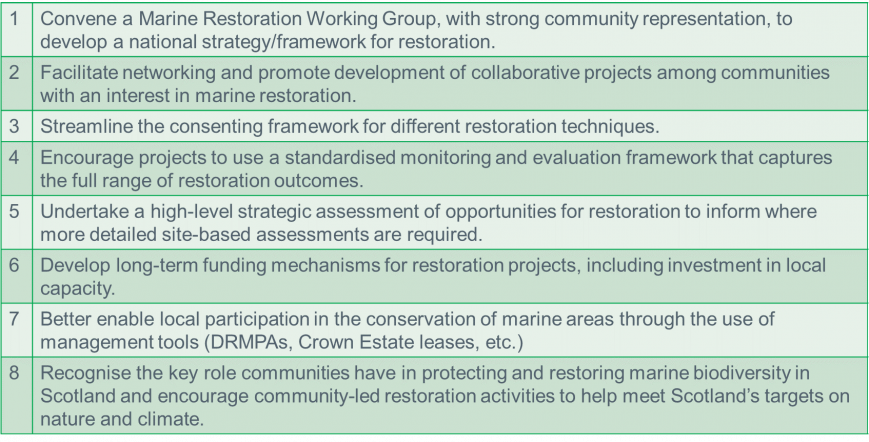

Recommendations from the report

What’s next?

Action is urgently needed to protect and restore Scotland’s marine environment and coastal communities must be at the heart of this effort. Many of the projects that have taken off are community-led and more are under development. There is invariably scope for greater collaboration and joint-working to achieve restoration at greater scales. As already demonstrated on the west coast, there is value in community groups learning from each other’s experiences. There is clearly a role for networks like the CCN to broker relationships between coastal communities across Scotland and facilitate knowledge-sharing.

Whilst community-led projects have developed to address local environmental challenges, with goals and objectives to suit their local context, there is potential to develop a shared vision for marine habitat restoration in Scotland.

It might be too early for this to happen, but a key first step would need to be a platform to facilitate dialogue on restoration and the integration of different priorities, beliefs and values across those concerned with marine protection. A dedicated forum should be established for taking this forward, but it needs strong community representation to remain responsive to local needs and concerns. Once a collective vision for restoration has been developed, this can then be used to help leverage the necessary changes in the regulatory, political and funding landscape for scaling up and delivering marine recovery across whole seascapes.

Read the full report here.

Tags: Community, Marine, Oyster, Restoration, Seagrass